Berkeley Tech Clubs Are Broken. Can They Be Fixed?

[Subject: An update on your application to Berkeley Technology]

Hi,

Thank you so much for applying to Berkeley Technology. We deeply appreciate you taking time out of your schedule to participate in our recruitment process. We received an incredible number of applications, but because we are constrained by our physical resources, the selection process was extremely competitive and as such we regret to inform you that we won't be able to offer you a position in Berkeley Technology this semester.

It saddens us that we cannot offer everyone a spot, but hope that it does not discourage you from continuing to explore the world of technology. We hope you apply again in future semesters!

Sincerely,

Berkeley Technology Executive Team

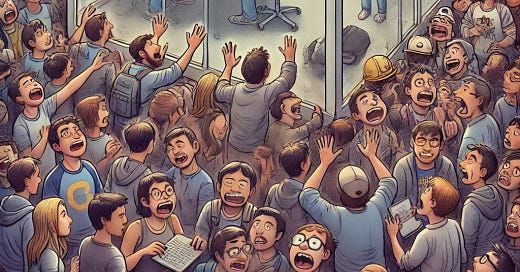

Over the last week, this email (or one very similar) has been sent out thousands of times. A large portion of Berkeley’s computer and data science majors will - or already have - written essays, attended coffee chats, gone to infosessions, participated in interviews, and completed technical projects in an effort to gain entrance to the 20-ish tech clubs on campus. Most of them - depends on the club, but between 80 and 98% - will fail.

The admissions process to tech clubs at Berkeley is incredibly streamlined. First, the advertisement phase. Each club will bring a stack of flyers, a branded tent, and a table to the center of campus and conscript their members into “tabling” for the club. This means that they’ll sit there for an hour and try to convince anyone who comes up that their club is the best one. They present a sanitized version of the club - instructed not to talk about anything potentially objectionable.

“What percent of people get in each year?” - Our admissions process is competitive, but we encourage everyone to apply.

“Do you have parties?” - We have social events each week for our members. There’s something for everyone!

“Do you admit seniors into the club?” - Of course, we will consider all applications.

The advertising process concludes with one or two infosessions, where you can get a more detailed idea of what the club is all about. You can meet the current members that are so excited about the club that they really wanted to talk to all the potential new members (surely they weren’t forced to come) and learn about all the exciting initiatives the club has, such as their semesterly retreat, the projects you could work on, and perhaps a new member education program with a pretentious-sounding name. They present a vision of not just a club of people with shared interests, but a community.

And so hundreds of people apply. They’ll write essays about how membership in this club will help them achieve their goals. [insert club] will allow them to finally find a group that they can relate to, people who they can work with and become friends with. Of course, they’ll actively participate in all of the unique parts of the club. They upload their resume, send it off, and hope that they’re lucky enough to receive an interview.

If they are in that fortunate quarter of applicants whose essays were well-liked by the recruitment committee (some sophomores who thought being in a “recruitment committee” sounded cool), they’ll advance to the interview rounds. Here, they’ll be asked a number of standard questions such as “What will you contribute to our club,” as well as some non-standard questions like “What animal best describes the type of programmer that you are?” If they give interesting enough answers, they’ll proceed to the technical round of interviews, where they might have to complete a project beforehand (surely no one would ever use ChatGPT for this) or answer some basic coding questions in the interview. Mostly, it’s another vibe check - the level of technical skill required to join the club is rarely particularly high.

And finally, after a round of often very intense deliberations, the club chooses a class of new members, to much fanfare. The group of 10-15 (sometimes as many as 25) will receive an excited email, or perhaps a prank call, welcoming them to the club. The newly minted members accept their invitations, and club recruitment season is over — for about eighteen weeks, just in time to do it all over again.

But let’s back up a little. How did we get here?

It would be really easy to write off the entire system of tech clubs as run by a bunch of narcissists who only care about being “prestigious” or elitist. I could end the post right here, with a little paragraph about how it’s this way because everyone in tech clubs sucks, and probably get plenty of agreement. It is true that there are some of those type of people in tech clubs. But as easy as it is to make fun of the insane recruitment process, a lot of good has also come from these clubs. Because of their existence, people have made lifelong friends, found groups of people that they really like, met girlfriends and boyfriends, learned technical skills, and had a lot of fun along the way. Most people in them are genuine about wanting to create a community - they might not be passionate about the technical thing their club is about, but they want to make friends, and are not, contrary to popular belief, solely motivated by being able to be in the most exclusive club.

(I should note here that I was in some tech clubs until I graduated a few months ago, and personally made lots of friends from the tech club system, including many of you reading this. I don’t believe I’m being unfairly biased in favor of them, but I want to be transparent.)

So how did this happen? How can these people, mostly with genuine motivations, create such an unfriendly, corporate system with a lower acceptance rate than MIT? The answer is based on a couple of factors.

Clubs at Berkeley are not easy to start

The average tech club at Berkeley has been around for maybe 5-10 years. In that time, they’ve developed a reputation on campus, have plenty of members and alumni, and typically have a project pipeline that allows them to consistently make between $10-20k per semester, though some clubs make significantly more.

A new club has none of these advantages, and is therefore much less attractive to potential applicants. When offered the chance to join a well-funded club with retreats to Tahoe, alumni who can refer you to internships, and custom Patagonia merch, why would you instead join the club that just started this semester and doesn’t have any of that? Potential club founders know that their club won’t be the first choice of most of the applicants they do get, and it’s difficult to break out of that cycle. In order to be successful, you have to offer something different than the other clubs - a different technology, the chance to have more control over the club culture, etc.

Even if you are successful at starting a new club, you probably won’t get most of the benefits. By the time your club is well-established, you’ll be about to graduate. If your goal is simply to have the tech club experience, to join a community, to make friends, you’re probably better off just joining one of the existing ones.

So people don’t start new clubs as often as would be necessary to get the acceptance rates to a reasonable level.

There is extremely high demand for clubs

The most popular tech clubs get several hundred applicants. If you’re a club with, say, 60 members, you cannot accept 500 people! You can’t even accept 50 people. If you expand the club much past 60, you lose the community that you had before - you can’t fit everyone in a typical classroom, holding a retreat is much more difficult, everyone won’t know everyone else. When the two choices are to deliver a good experience to 3% of your applicants, or a bad one to 100%, it becomes clear that you have to devise some way of filtering out the applicant pool.

So you do it the only way you know how - essays, interviews, modeling your process off of the things you’ve applied to in the past like colleges and jobs. This means that your system is going to fall prey to the same weaknesses that those systems have: probably there will be some nepotism, for example. But of the ways you could pick the lucky 3%, it’s not the worst one.

At its most basic level, the whole club system is a supply and demand problem. There is low supply (new clubs are hard to start), and high demand (lots of people want to join the existing clubs). And so the result is a highly competitive system to gain access to these clubs. It’s the same reason that it’s hard to get internships, research positions, or to get into college - it just seems more insane when applied to something like “college clubs,” which offer a lot fewer clear benefits. (Not to mention the fact that joining clubs is always one of the top recommendations when people ask “how do I make friends,” and so the competition in this system makes people feel like they’re being gatekept from even the ability to make friends).

Okay. So we’ve established that the current process is crazy, and explained the forces that led to its formation. The next logical question - can it be fixed? Should it?

I really do think there’s something worth saving here. Berkeley’s tech clubs may be ridiculously competitive to get into, but people do find communities within them. Hundreds of people every year enjoy being part of them, for real, non-elitist reasons. People feel more connected to the tech community, and there are real benefits from having 60-person clubs instead of 600-person clubs that anyone can join (and which as a result have a much weaker culture).

Of course, it’s easy to say generically that they should just be made better, without explaining how. So I’ll explain the ways in which I would go about improving these clubs and their reputation, if I had the power to.

Get rid of the clout chasers

Most members of tech clubs are not clout chasers, but most clout chasers (at least those in computer science) are members of tech clubs. It’s unfortunate, but there’s definitely some people out there who do join just for a line on their resume, or because it makes them feel like they’re better than other people. Some clubs have more than others, and I won’t name which ones but it’s not too hard to find out. These are the worst types of tech club members, and the reason the stereotypes exist. They take the resources of the club and give nothing back.

Clubs should aggressively screen for these sorts of people in their interviews. It’s hard to do - they won’t show their true colors until they get accepted. But it’s worth it. Part of running a club is that you need your members to buy in - they have to be excited to participate in the community, and in return, they get the benefits of the club. If even one or two members upset that balance, by taking the benefits and not caring about the community, the rest of the members start to think that maybe the community wasn’t that important to begin with. It doesn’t take very many to completely change the culture for the worse.

Treat clout chasers like bedbugs - if you find one, you need to figure out how they got in and make sure it doesn’t happen again. Don’t be afraid to kick them out of the club, even if they’ve technically done the minimum required thing to stay in.

(are you, the reader, a clout chaser? none of my subscribers are! but some people who don’t subscribe to this blog are. just saying)

No more nepotism

A lot of people have the idea that nepotism is the only way to get into tech clubs - if you don’t know one of the members, you definitely won’t get in. I do want to say that many clubs do make efforts to avoid nepotism - I’ve been in a lot of recruitment deliberation meetings, and in many cases there is only a slight boost for someone who is friends with the leadership members. But I think more needs to be done. Of course, when you first start a club, the members are likely going to just be your friends. But if you’ve got a club with a competitive, theoretically unbiased application process? You need to take extra steps to ensure that you aren’t unfairly biased in favor of people you happen to know, even if they’re qualified to join.

It’s really easy to say “Well, I’ve known Steve for a while, I know he is a hard worker and he’ll definitely be a great member. The only information we have about Bob is based on two short interviews, even though he did well. Anyone can pretend to be a good member for 45 minutes! So we have to take Steve.” It’s not the worst form of nepotism - Steve is probably legitimately a good candidate - but you have information about Steve that you had no chance to learn about Bob, which biases you against Bob. If you took all the new members based on who you knew the most about, you’d never take anyone who didn’t already have a connection to the club, all while saying you’re unbiased because you didn’t accept anyone obviously unqualified. And that will lead to cliques of people who already know each other, making the whole experience worse and hurting the reputation of all tech clubs as places where “you just have to know someone.”

Start spinoff clubs

This is my most speculative idea, and it would probably be harder to actually accomplish than it seems in theory, but I still think it’s worth mentioning. As I said above, it is very difficult to quickly start a completely new club from scratch. However, I think that one thing that clubs should do more of is to create “parent” organizations which have some control over multiple clubs. For example, the two machine learning clubs which get the most applications each year are Machine Learning @ Berkeley and Launchpad. There’s way more demand for machine learning clubs at Berkeley than the 20ish students that get into one of these each semester. These two clubs could work together to create a parent organization which allows for the creation of new machine learning clubs more easily1. The first semester, you could take the pool of applicants to each of the two clubs, and offer 40 of them the chance to form their own club, with help from ML@B and Launchpad. Many would probably accept - and with this help, it wouldn’t be long before the new club also had a long list of applicants.

What do the clubs that create this organization get out of it? They get the chance to do something good for the community, but more selfishly, they get another club to do cross-club socials with, a larger referral network, and a better reputation. The difficult question is funding, which might be difficult in the first semester, but after that I imagine most of the clubs would be self-sustaining with advice from the parent clubs on how to get sponsorships or projects.

I think you could even do this with clubs that aren’t particularly related. Most tech clubs offer a similar experience, and the people applying don’t care much about where they get it from. You can’t be too weird or you won’t get many applicants, but there’s certainly room for more generic coding clubs that pretend they’re super different from the others.

Increase transparency

One of the parts of these clubs that I don’t like is that when recruiting people for the club, members often go a little overboard in trying to get as many applicants as possible. If your club is unlikely to accept juniors, you should tell people this (or decide to accept more juniors). Does your club have a low acceptance rate? Instead of refusing to give any details about the acceptance rate, at least give people a rough number so they know their chances. If someone would have applied, but decides not to because the acceptance rate is 5%, is that really someone you want? I understand the idea that every additional applicant is a potential member, and it really does feel good to get 400 applicants to your club. The more transparent you are about the process, though, the better your applicants are going to feel when applying, and the more likely they are to apply again.

I’m making the argument here that you should do this because it benefits your club, but also, come on. You are not a corporation, you have no obligation to shareholders to get a certain number of applicants every year. Be a nice person and be honest about your application process. You don’t have to put a big banner that says your acceptance rate on your tent, but don’t get people’s hopes up and then throw away their application. I think you should do this even if other people/clubs are not, because it will make your applicants’ lives just a little bit better, and that adds up.

Of course, I can’t actually do any of this, because I graduated four months ago. Instead, I’m writing this while I hopefully still can have a little bit of influence to encourage you to do it. If you are still at Berkeley, especially if you have a leadership position in one of these clubs, go and make some change! Even if you think my solutions are bad, hopefully I’ve at least convinced you that there is a problem, and you can come up with your own ideas. It won’t have immediate results, but I think if everyone leaves the clubs better than they joined, there could be a lot of change in a few years. The nature of college is that every 4 years, there’s a (mostly) completely different set of people than there were before. So it’s possible to have dramatic change in not much time, even though you sometimes won’t be around to see the results of that change.

And I don’t mean to say that you won’t see any results at all. If you kick out toxic people, for example, that will start improving the culture immediately. In my time at Berkeley I was in clubs that made dramatic culture changes in just one semester, both positive and negative. A small amount of targeted effort can make a big difference - and I really do hope that in another 4 years, when everyone I went to school with has graduated, someone comes across this post and can’t imagine it ever having been a problem.

Yes, the ASUC has a rule which says you can’t just create new clubs about the same thing, but you could introduce subtle differences or something to get around that.